02 · Group Key Agreement with BeeKEM

| Author | Ink & Switch |

|---|

- BeeKEM in isolation provides Forward secrecy, but Keyhive as a whole does not. That’s because users require access to an entire document and Keyhive is used to encrypt that document in chunks. If you can decrypt a chunk, you will gain access to the key for decrypting the previous chunk (as described in an earlier lab note)

BeeKEM

In this section, we’ll see how BeeKEM works in more detail.

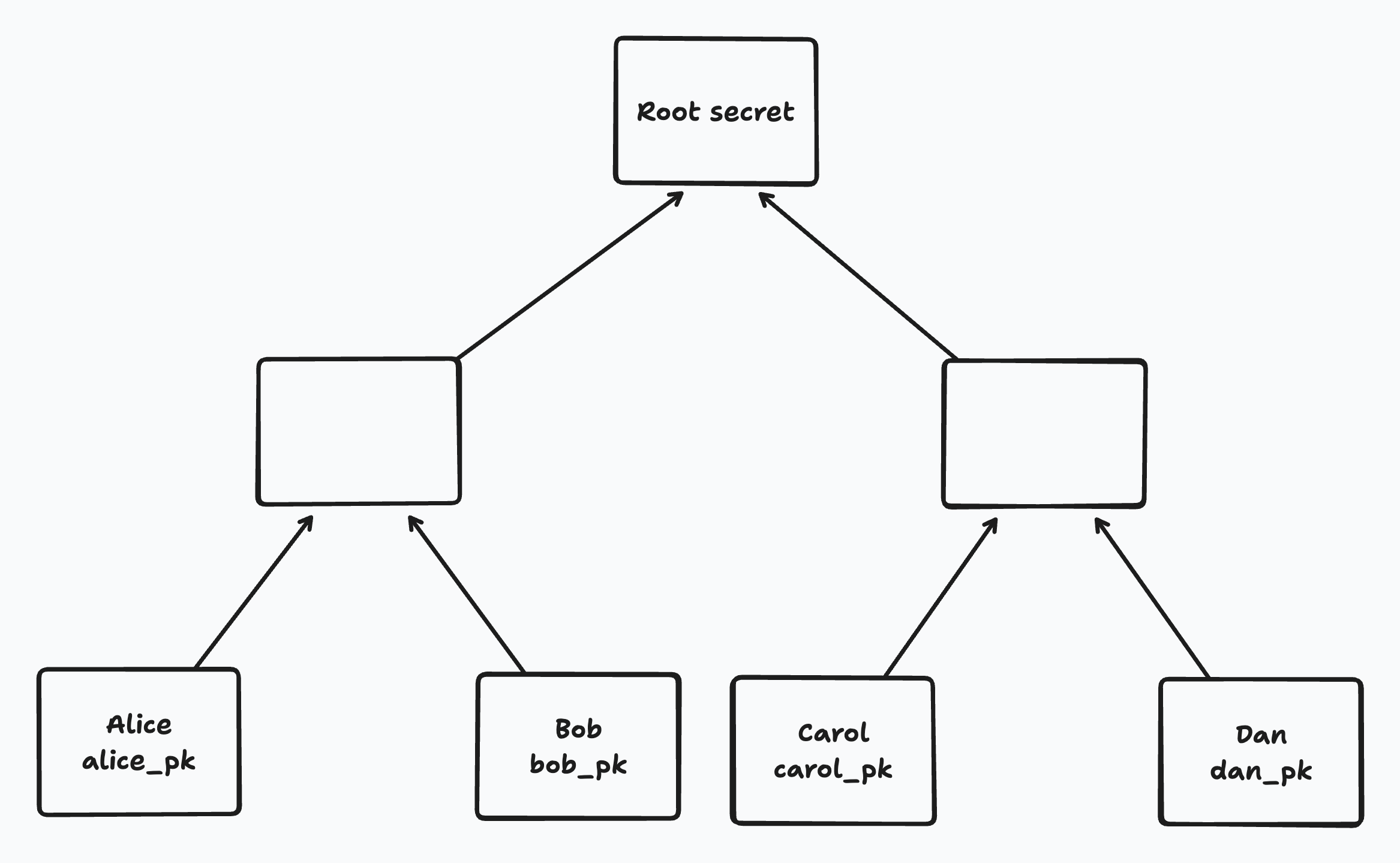

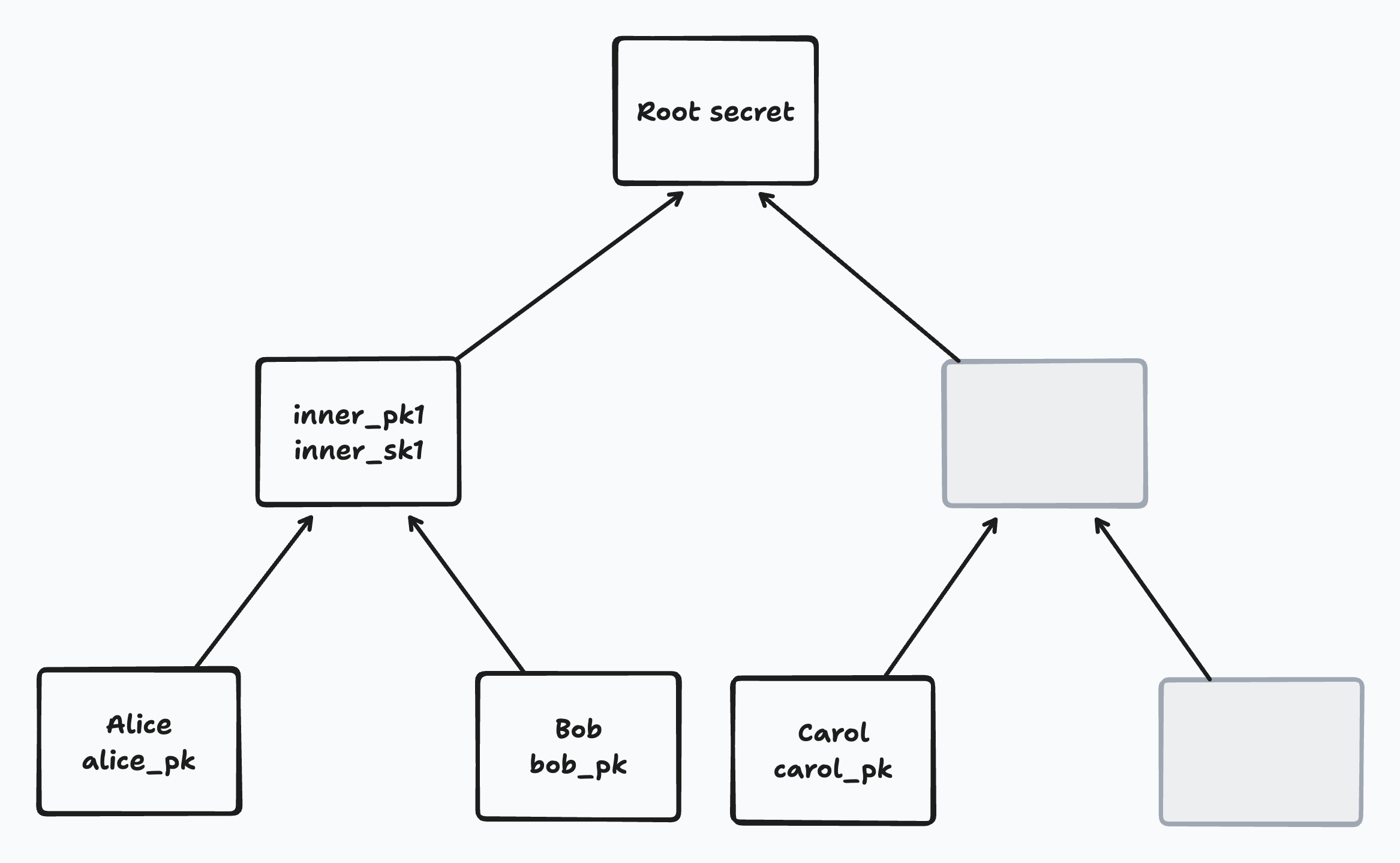

In BeeKEM (as in TreeKEM), the current group secret is stored encrypted at the root node of a binary tree. We’ll call this the “root secret”. The root secret is used for encrypting and decrypting document chunks shared with our group over the network[^5].

Each leaf of the tree corresponds to a member of the group and contains its ID and latest Diffie-Hellman (DH) public key. A member’s ID is persistent over time but each member will periodically rotate its DH public key. When a member rotates its DH public key, that will cause the root secret to change as well. Thus, member key rotations help provide post-compromise security. From the point of view of an adversary, they introduce fresh randomness.

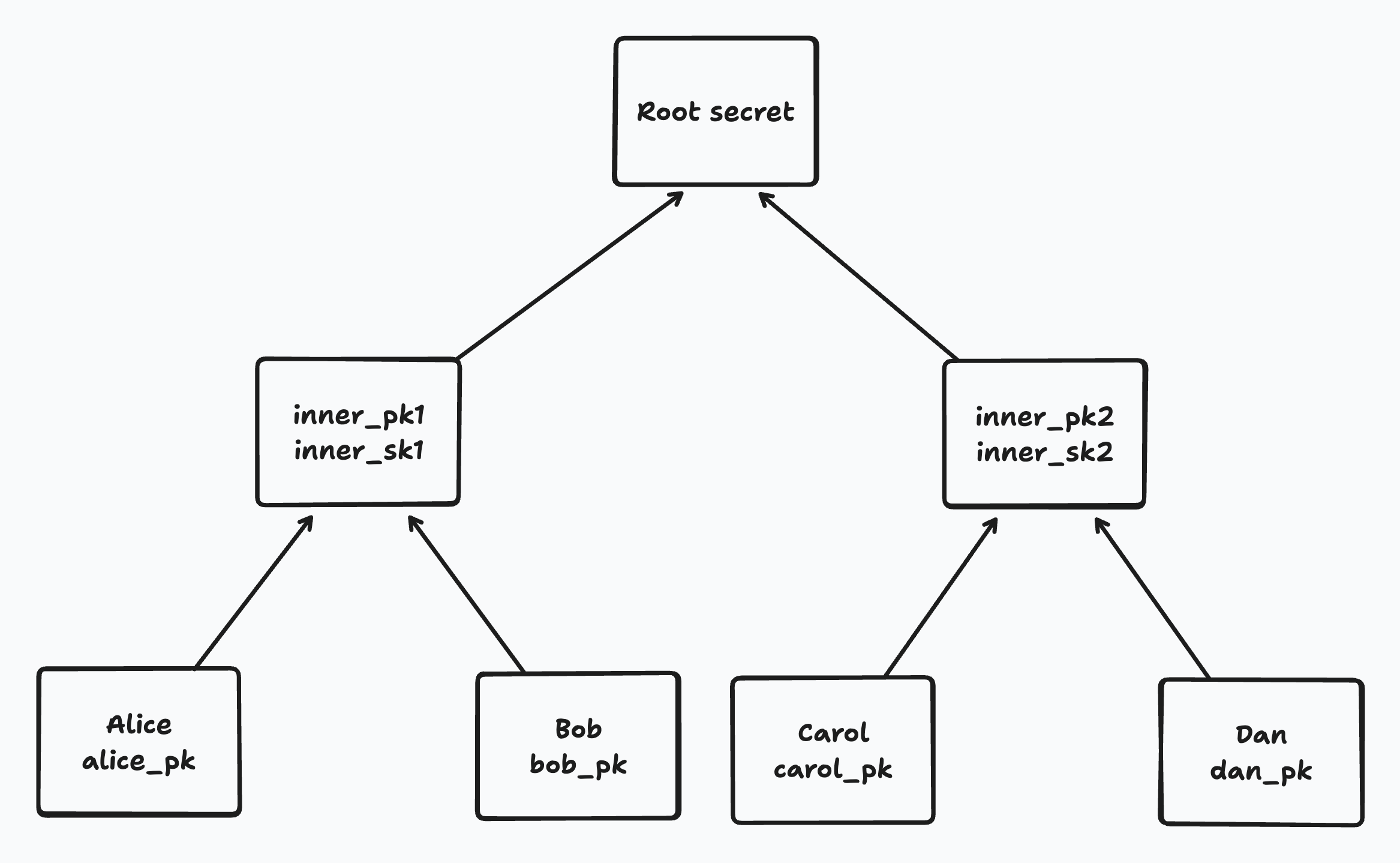

Each leaf has an implicit secret known only to the corresponding member (i.e. not stored in the tree). All other “inner” nodes in the tree contain a DH public key for that node and a corresponding secret key that is stored encrypted at the node.

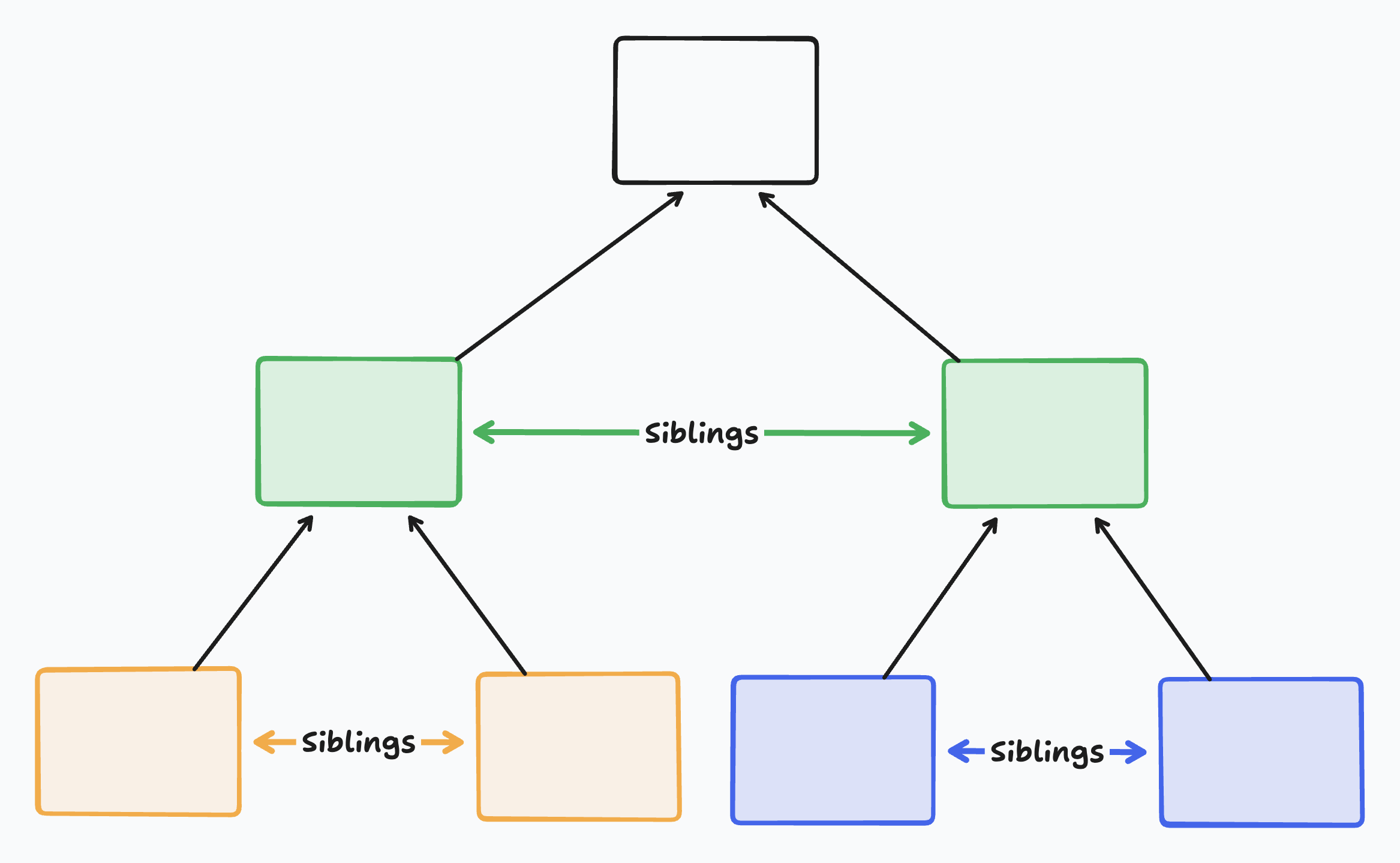

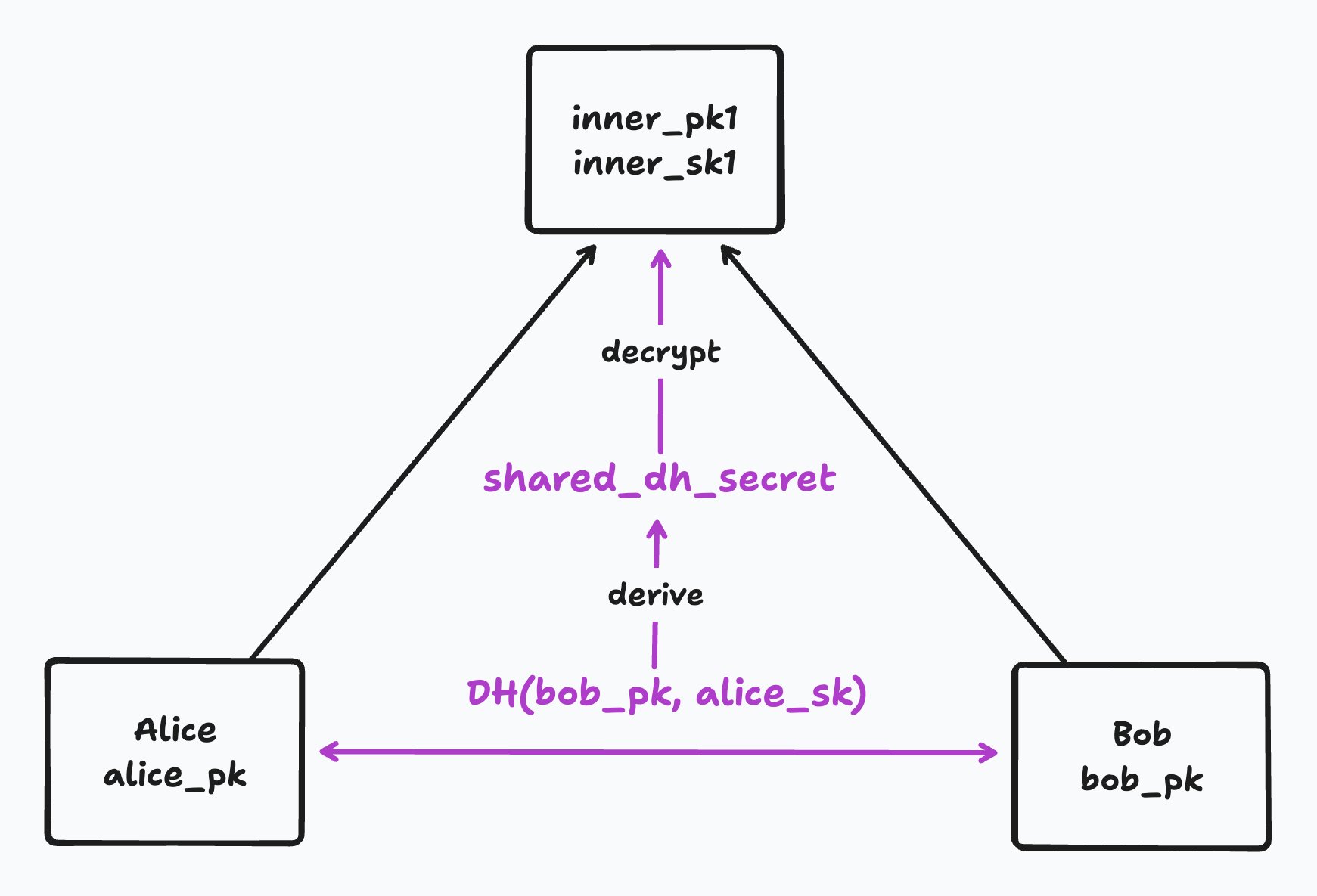

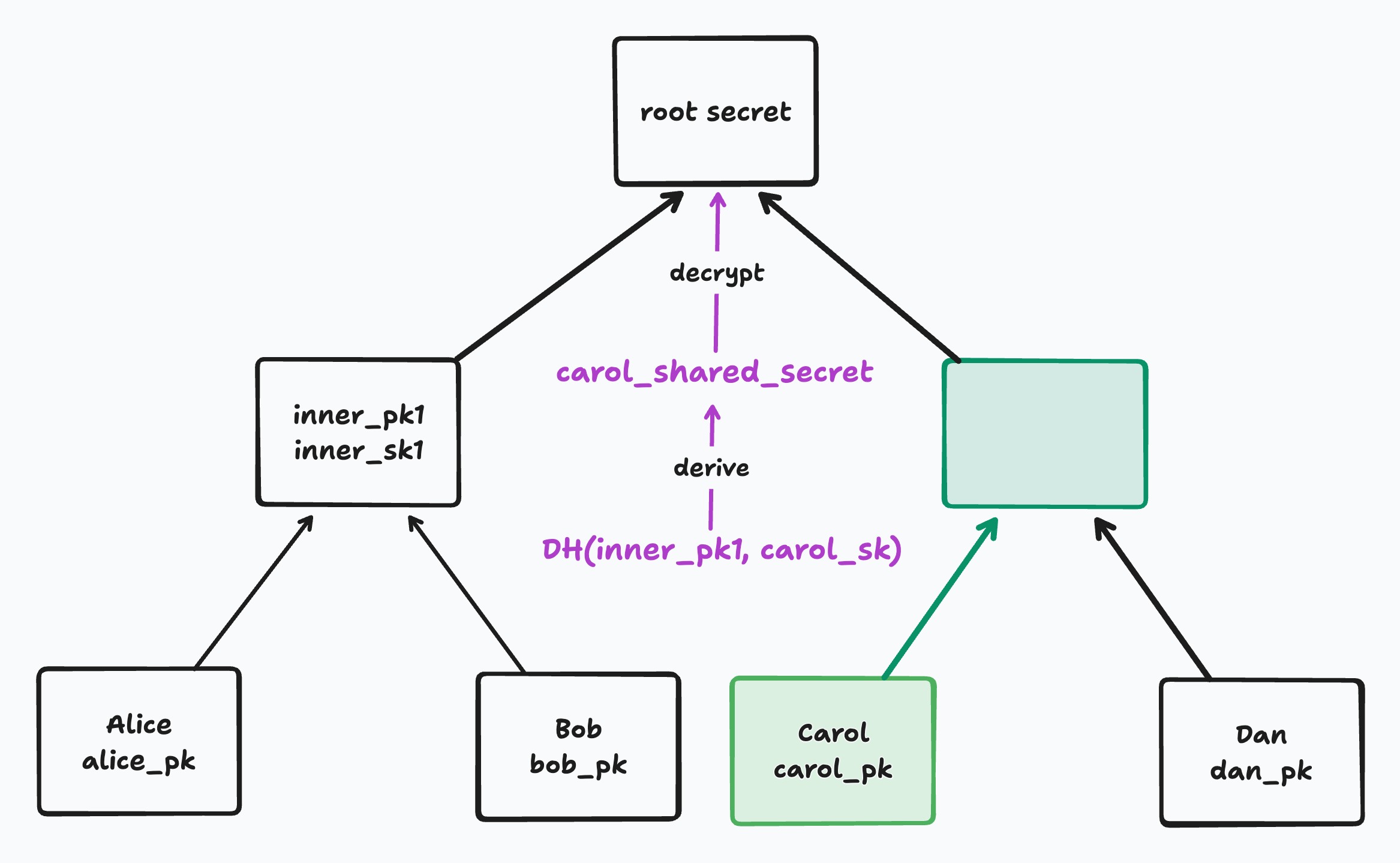

Each node in a binary tree has a single sibling node, as illustrated in the following diagram:

When encrypting or decrypting a new secret at a parent node, a child node performs a Diffie Hellman key exchange with its sibling. That means it will use its sibling DH public key and its own secret key to derive what we’ll call a “shared DH secret”. The shared DH secret is used to encrypt and decrypt the new secret at the parent.

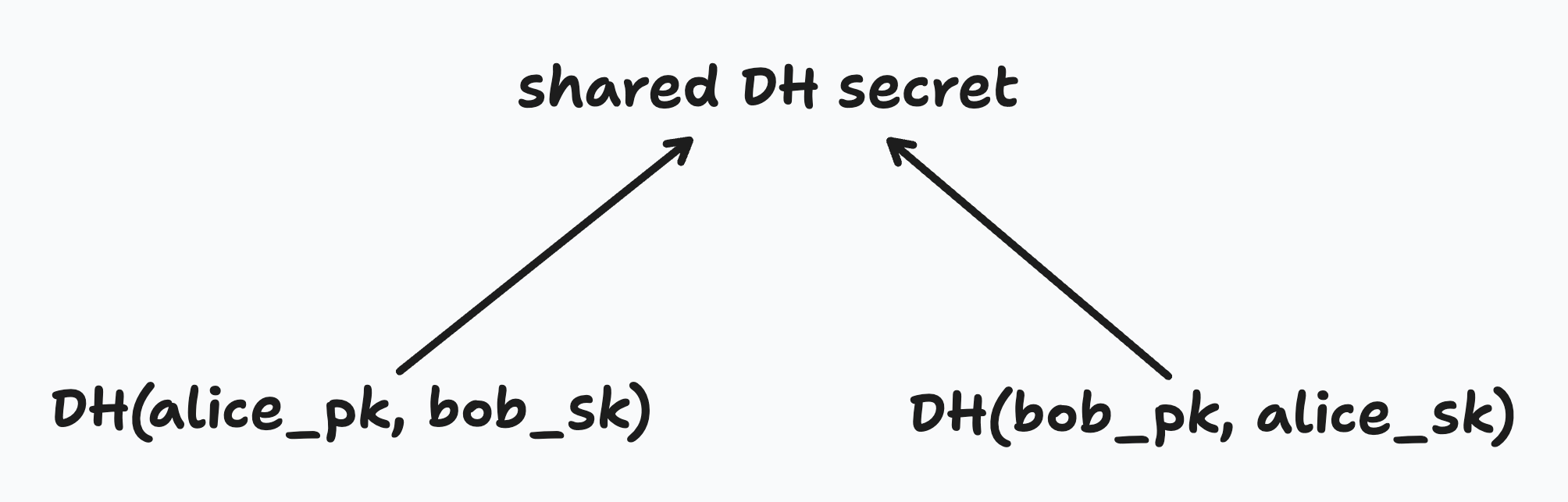

A brief (simplified) aside on how Diffie Hellman key exchange works. Imagine Alice and Bob each have their own DH public keys (alice_pk and bob_pk) and DH secrets (alice_sk and bob_sk). If Alice combines her DH public key with Bob’s secret key, she can derive a shared DH secret. If Bob combines his DH public key with Alice’s secret key, he can derive the same shared DH secret. In this way, they can agree on a shared secret just by exchanging their public keys in the open.

We use this same principle to derive a shared DH secret for any sibling pair in our tree. For example, to decrypt Alice’s parent node, Alice can use its secret alice_sk and its sibling’s public key bob_pk to derive a shared DH secret. It can then use that shared secret to decrypt the secret at the parent node.

In pseudocode, this might look like:

shared_dh_secret = DH(bob_pk, alice_sk)

parent_secret =

encrypted_parent_secret.decrypt_with(shared_dh_secret)

That parent secret can in turn be used for a Diffie Hellman exchange with the parent’s sibling’s DH public key.

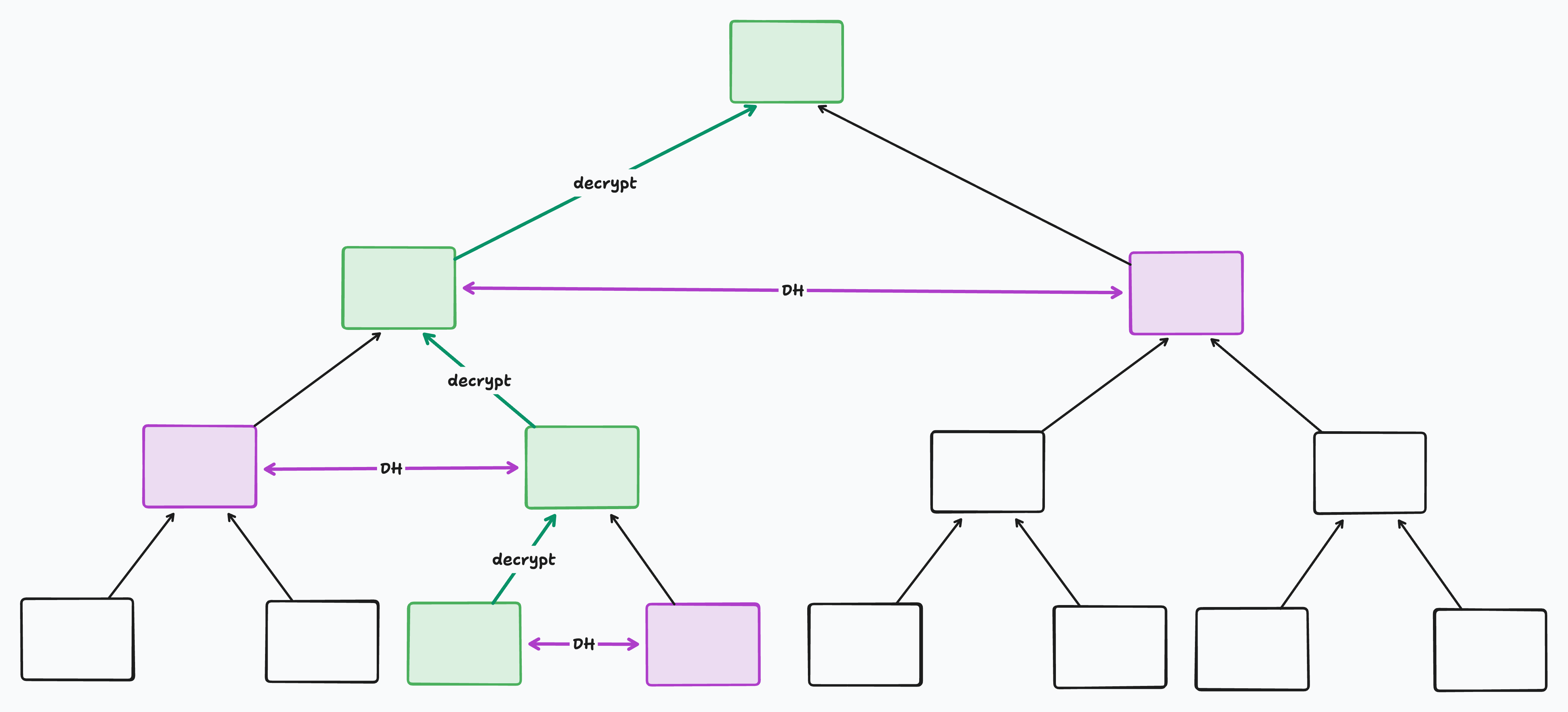

For a member to decrypt the root secret, it must start from its leaf and traverse the tree one parent at a time until it reaches the root. The sequence of nodes from leaf to root is called that leaf’s “path”. At each node in its path, it will derive a shared DH secret with its sibling to decrypt the secret at its parent. Once it’s decrypted the root secret, it’s done.

In the following diagram, the decrypting leaf’s path is marked in green. The siblings used as Diffie Hellman partners along the way are marked in purple:

There are three mutating operations that can be performed on the tree: Update Key (i.e. key rotation), Remove Member, and Add Member. Let’s look at these in more detail.

Update Key

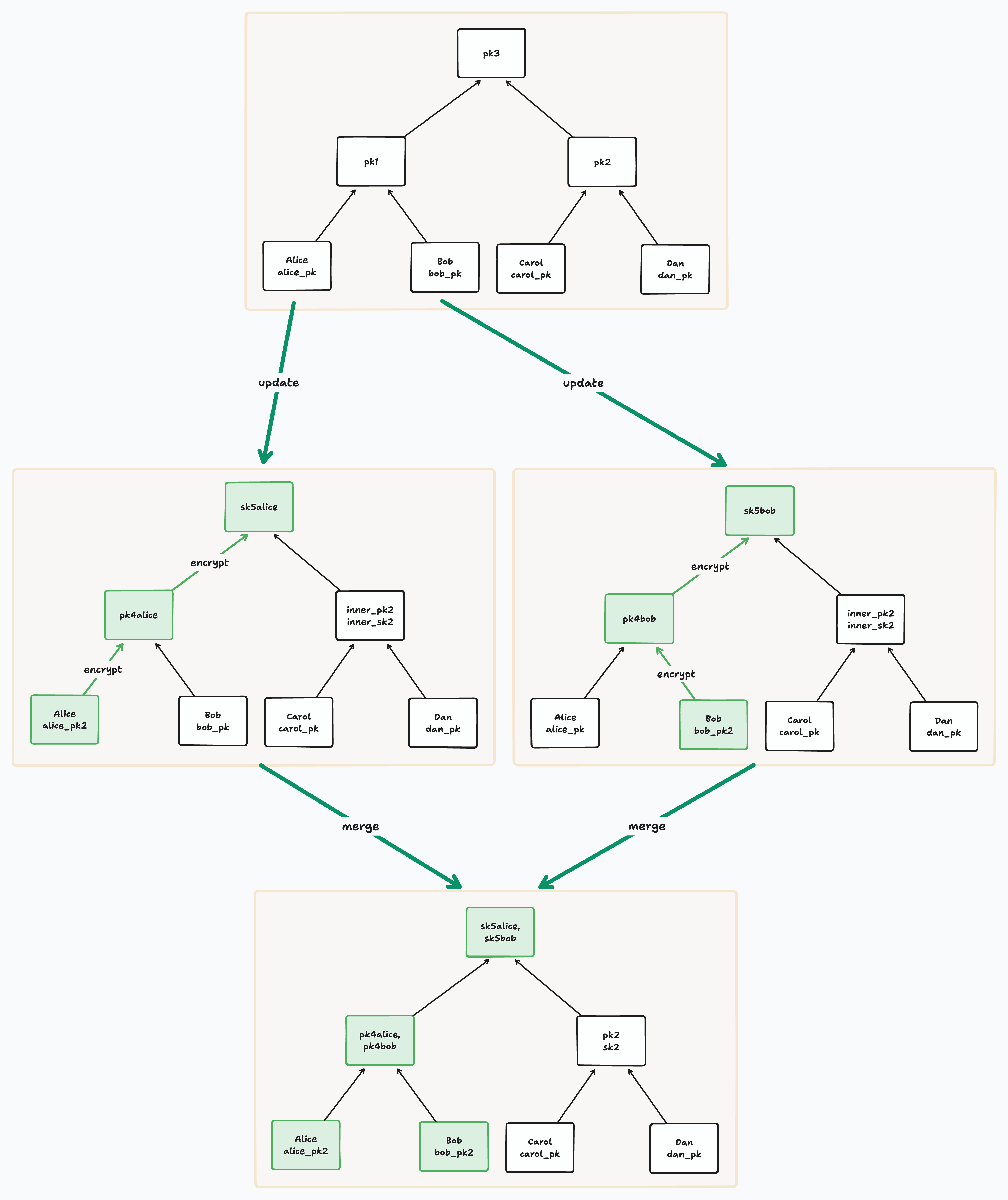

Every member must periodically update the DH public key at its leaf in order to guarantee post-compromise security. When we update our leaf DH public key, we must then update the secrets for all the nodes on our path, eventually updating the root secret for the entire group.

Before traversing our path, we can derive a sequence of path secrets by applying BLAKE3’s key derivation function to an initial secret once for each node on the path. As we move up each parent on our path, we will encrypt the next derived secret and store it on that parent.

In order to encrypt the secret for a parent, we use Diffie Hellman key exchange as described above. We then derive a new Diffie Hellman public key from the secret for the parent, and store both that new DH public key and the corresponding encrypted secret at the parent.

In pseudocode:

parent_secret = derived_secrets[next_idx]

shared_dh_secret = DH(child_sibling_pk, child_sk)

encrypted_parent_secret =

parent_secret.encrypt_with(shared_dh_secret)

parent_pk = DH_pk_from(parent_secret)

parent_node.insert(parent_pk, encrypted_parent_secret)

Later on, when the sibling wants to decrypt that parent secret, it can do Diffie Hellman the other way, using the encrypter node’s DH public key with the sibling node’s secret to derive the same shared DH secret that was used to encrypt the parent.

shared_dh_secret = DH(encrypter_pk, sibling_sk)

encrypted_parent_secret = parent_node.encrypted_secret

parent_secret =

encrypted_parent_secret.decrypt_with(shared_dh_secret)

Membership Changes

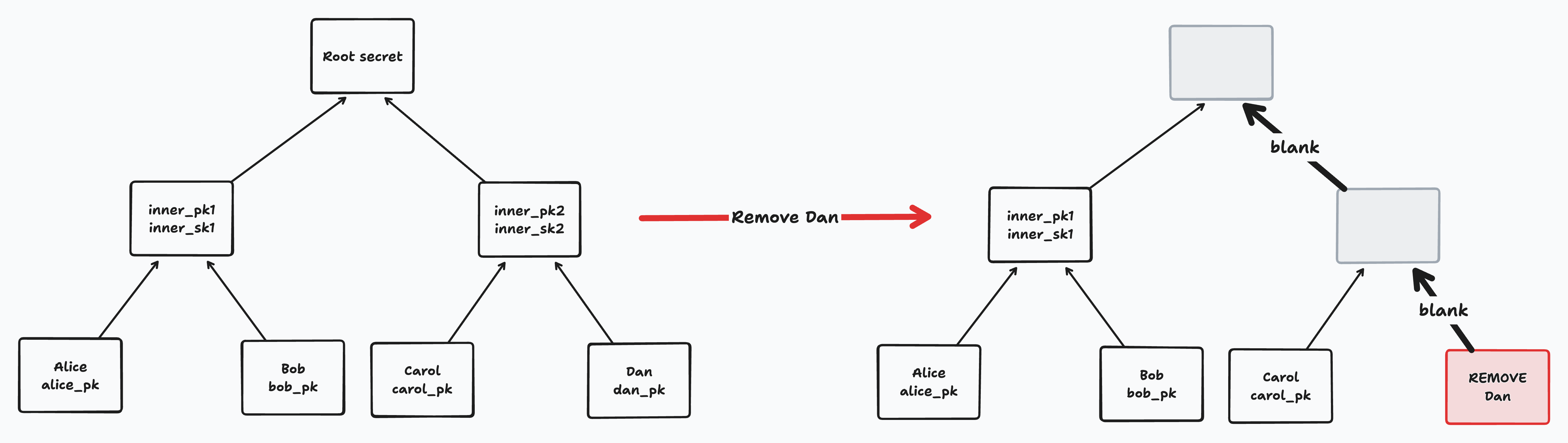

In order to explain membership changes, we must introduce the concept of “blanking” a node. Blanking a node means that we remove all key and secret information from that node. If the root node is blank, then the tree does not currently hold a shared group key. Some nodes are blanked after membership change operations, and all leaves beyond the last member leaf on the right are blank.

If a tree has a blank root, then at least one member must perform an Update Key operation to restore a root secret. An update will replace all blank nodes on its update path with key information.

When we perform a Remove Member operation, we first blank the leaf corresponding to that member. We then blank the entire path from that leaf up to the root node.

Notice that if a removed member performs an update concurrently with its removal, we need to ensure that the update does not survive (or else the member will continue to have access to the root secret). When merging concurrent removes with other operations, BeeKEM ensures that the remove paths are blanked after all other concurrent operations are merged.

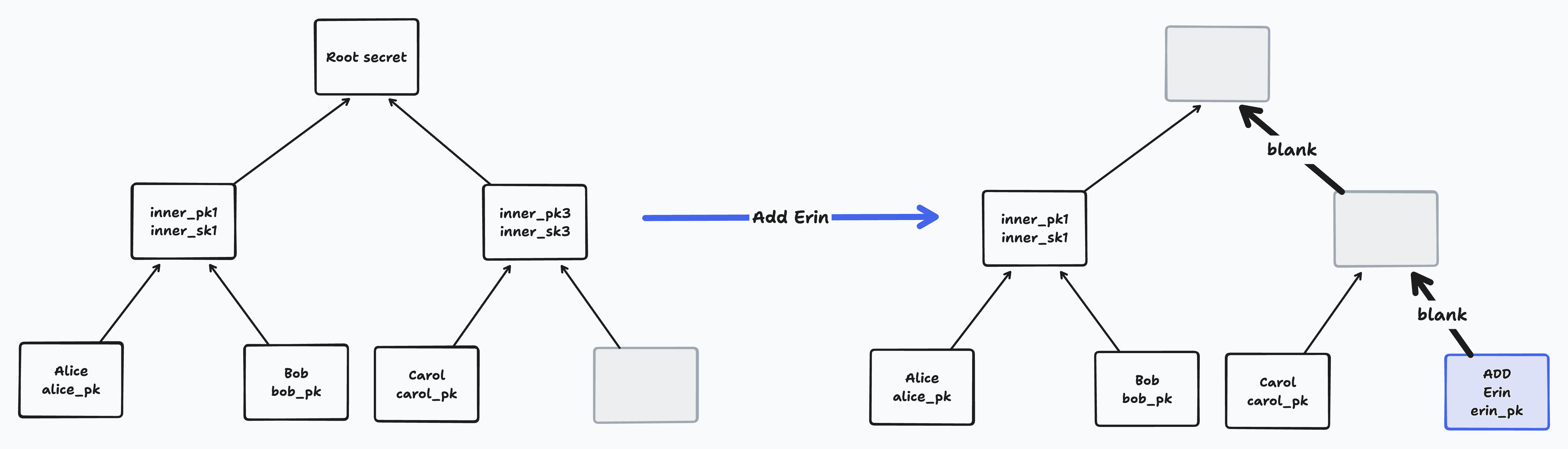

When we perform an Add Member operation, we add the new member’s ID and public key to the next blank leaf on the right. We then blank the path from that leaf to the root.

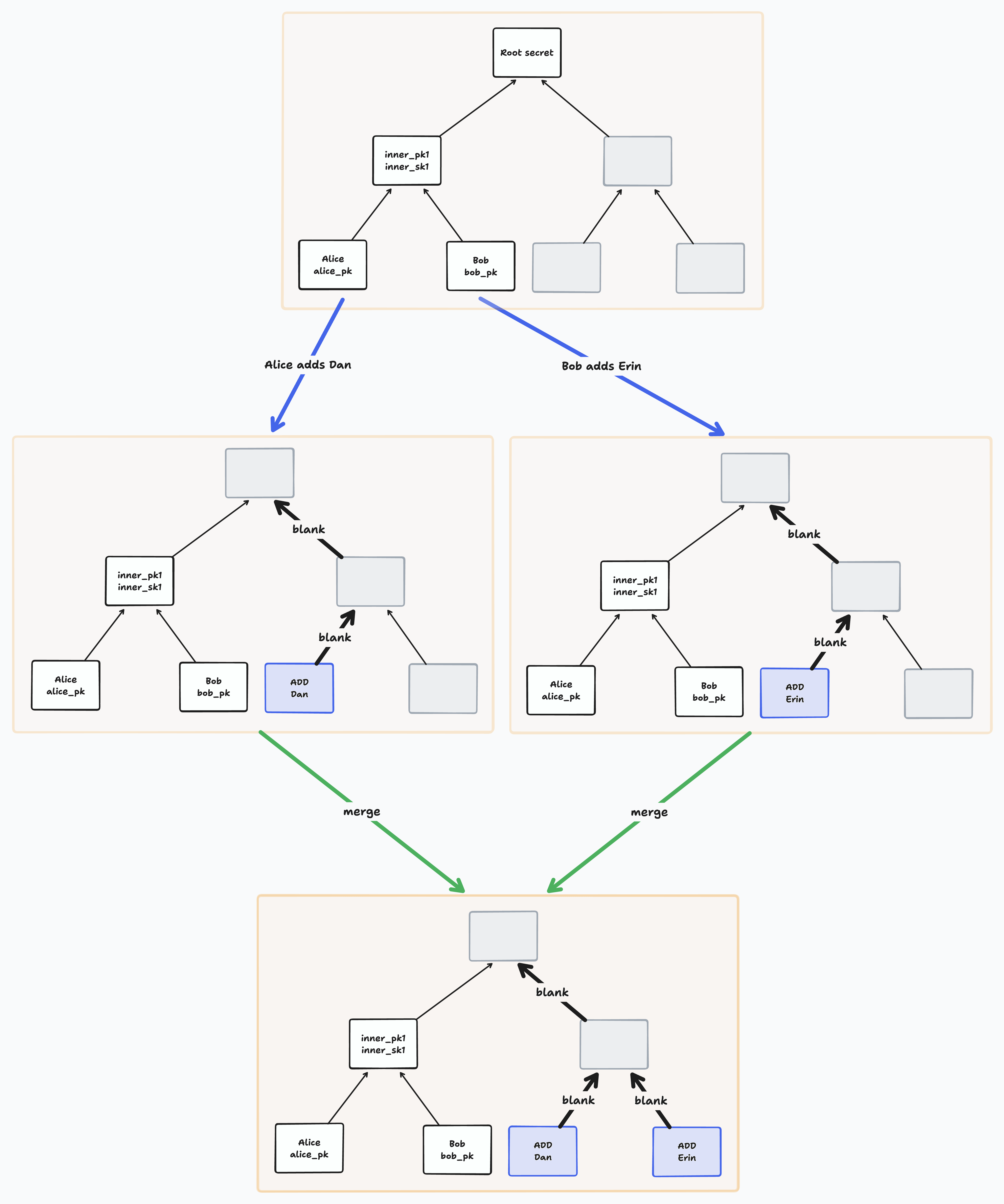

Notice that if two members add a member concurrently to the same tree, they will add them to the same leaf. BeeKEM resolves such conflicts on merge by sorting all concurrently added leaves and blanking their paths.

Handling Blank Nodes on Update and Decryption

So far, we’ve assumed that every node has a sibling with key information. That’s what allowed us to use Diffie Hellman to derive a shared DH secret. But what happens when a node’s sibling is blank?

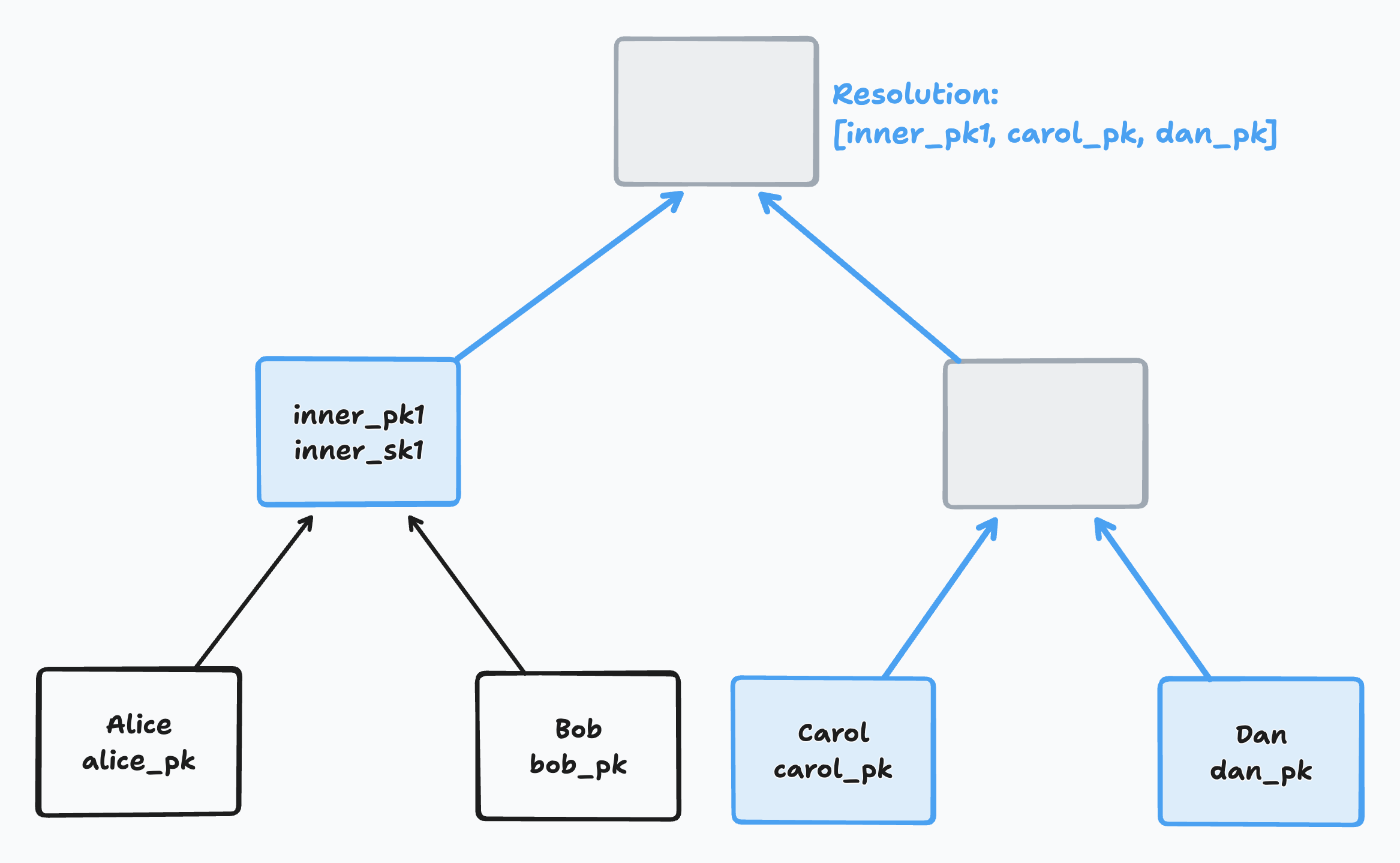

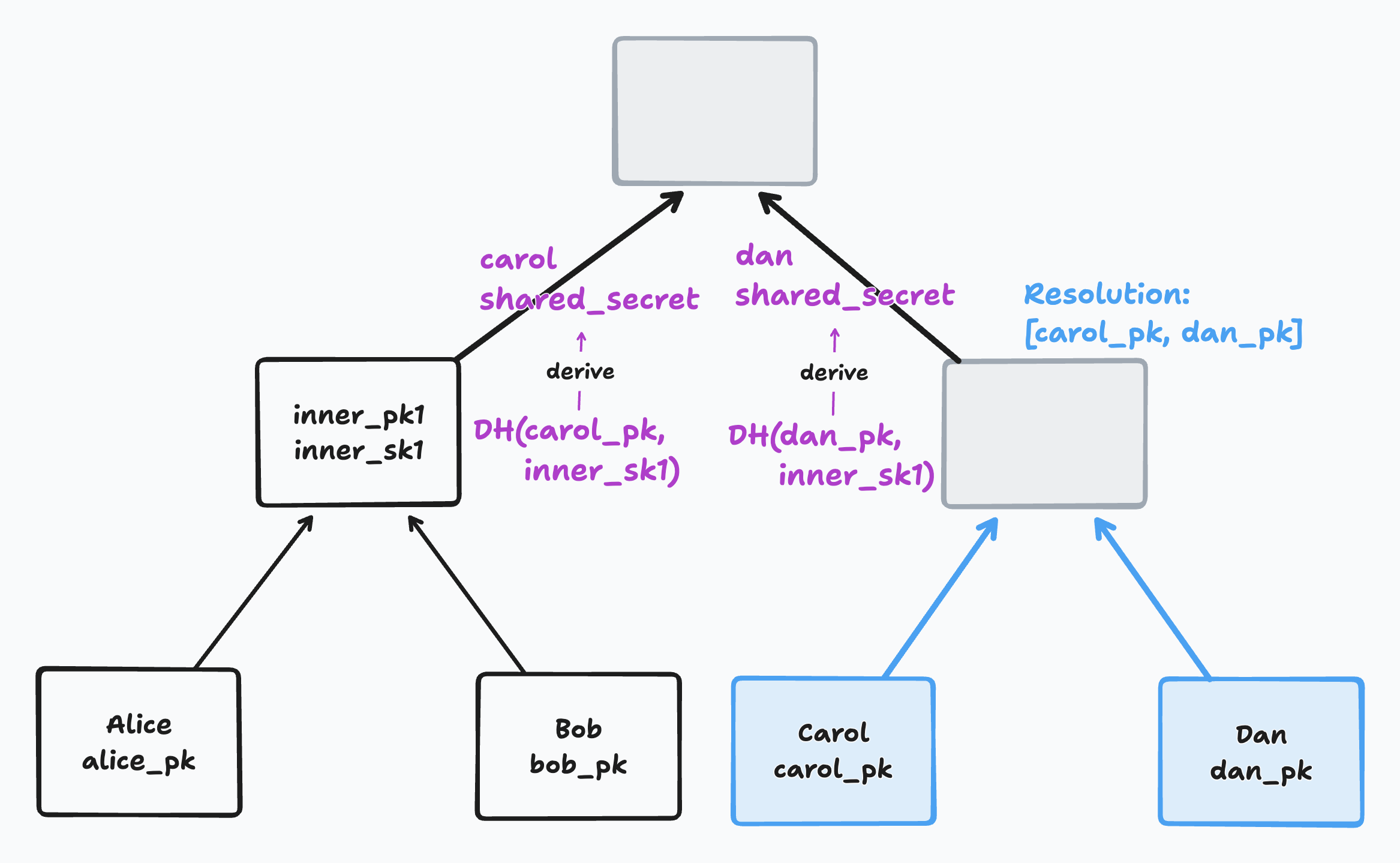

In that case, we must find the blank node’s resolution. A node’s resolution is the set of its highest non-blank descendents. Here’s an example:

If you have a blank sibling, you must do a separate encryption of the new parent secret for every member of your sibling’s resolution. For each of those members, you use its Diffie Hellman public key with your secret to derive a shared DH secret. You then encrypt the new parent secret using that shared secret and store it for that member.

This means that if the resolution of a sibling node contains 5 members, you will need to store the parent secret 5 times, each one encrypted for a separate member.

The worse case scenario is if the entire inner tree is blank. Encrypting a new path will no longer be a logarithmic operation since every leaf will be contained in the resolution of some blank node on your path. Instead, the cost will be linear in the number of leaves: you will have to perform a separate encryption for every other leaf somewhere on your path.

When decrypting a leaf with blanks on its path, you simply skip those blanks. This works because the highest blank in your path will contain its last non-blank descendent in its resolution. So when you encounter a blank on your path, you hold onto the last secret you’ve seen and start skipping. When you eventually get to a non-blank node, you’ll use that secret you’re holding onto to derive the shared DH secret you need to decrypt the non-blank parent.

Handling Concurrent Updates with “Conflict Keys”

Keyhive assumes that concurrent operations can be merged in any causal order. Concurrent updates will always have some overlapping nodes in their paths (at least the root is shared by all paths). How does BeeKEM resolve these conflicts?

We must first consider our potential vulnerabilities. Imagine that an adversary has compromised a group member and their leaf secrets. They can use a compromised leaf secret to decrypt the root secret at some point in time. Recall that knowing a leaf secret means you can decrypt all of the inner node secrets along your path.

If an adversary knows the secret for a leaf, it’s possible they will continue to be able to decrypt the group secret even if that leaf is rotated during a future concurrent update. This depends on how we handle merging concurrent updates.

If we just naively pick a winner for updates to a series of overlapping nodes, then the new information added by the loser’s key rotation will no longer be necessary to decrypt the root secret. We effectively forget that information.

Notice that the winner used the outdated keys from the loser for its update (since the winner’s and loser’s updates were concurrent). That means an adversary with the loser’s outdated leaf keys will still be able to decrypt the winner’s nodes. Subsequent updates by other leaves that only intersect with the winner’s path will also fail to exclude our adversary.

In BeeKEM, when merging concurrent updates, we ensure that all updates contribute information along their entire paths. We keep conflicting information around at each node until it is overwritten by a causally subsequent operation (or blanked by a membership change).

If two leaves update the same node concurrently, then they would have each written a distinct Diffie Hellman public key and encrypted secret to that node. In this scenario, we call these “conflict keys” and store them both when merging conflicts.

Imagine a member subsequently updates the tree. If a node on its leaf’s path has a sibling with conflict keys, this means there is an unresolved merge at that sibling. An adversary could have access to both sides of the corresponding fork. So it wouldn’t be secure to use those conflict keys for Diffie Hellman. Instead, we take the resolution of the node, just as we did with blank nodes. We then separately encrypt the secret for every DH public key in the resolution, again just as we did with blank nodes.

This means that for BeeKEM we update the definition of the “resolution of a node” to mean either (1) the single DH public key at that node if there is exactly one or (2) the set of highest non-blank, non-conflict descendents of that node.

If we merged in both sides of a fork, then we know we’ve updated both corresponding leaves with their latest rotated DH public key. Since taking the resolution skips all conflict nodes, it ensures that we integrate the latest information when encrypting a parent node. That’s because any non-conflict nodes have successfully integrated all causally prior information from their descendents.

This means an adversary needs to compromise one of the latest leaf secrets to be able to decrypt an entire path to the root. Even knowing outdated leaf secrets at multiple leaves will not be enough to accomplish this. An honest user, on the other hand, will always know the latest secret for its leaf.

During a future update (key rotation), if you find a conflict key node on the path you’re updating, you can remove all conflict keys at that node and replace them with a single new public key and encrypted secret (as with normal parent encryption). That’s because your update operation is the causal successor of all the operations that placed those conflict keys. This means your tree contains the necessary information from all of those past updates, which is integrated into your update.

BeeKEM’s approach comes with two downsides. First, before conflicts are resolved by subsequent updates or blanks, we must store extra information at each conflict node. Second, conflict keys add extra encryption and decryption overhead. In the worst case, where the tree is populated with the maximum number of possible conflict keys, the space cost would be n log(n) (as opposed to the best case of 2n). The time cost in the worst case would be linear (as opposed to logarithmic), as when the tree is maximally blanked. Our current set of benchmarks reflect these time costs when we intentionally exercise our worst cases.

BeeKEM provides Keyhive with a Continuous Group Key Agreement protocol that is well-suited to distributed local-first applications that require end-to-end encryption for groups on the order of thousands of members. It exhibits logarithmic performance in the common case with linear worst case. And it provides both forward secrecy and post-compromise security.

In the future, we plan to write a paper explaining this protocol and its security and performance characteristics in more detail. But hopefully this has given you a sense for how it works.

[^5]: More precisely, we use the root secret as one input into deriving an “application secret”. It is the application secret that is directly used for encrypting and decrypting document chunks. There can be multiple application secrets derived from one root secret, but each application secret is used to encrypt exactly one document chunk. Updating the root secret provides post-compromise security by ensuring no prior key can be used to derive application secrets associated with it. We are glossing over these details in this lab note since they strictly speaking happen outside BeeKEM, which is concerned with group agreement on the root secrets.